Words such as serve, protect, fidelity, bravery, integrity, justice, and courtesy are contained in the slogans and mottos of approximately 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the United States. Every day (and night), brave men and women don uniforms, business attire, or street clothes to leave home and take on the role of protecting the citizens and property of our communities. Like the men and women of the military, their lives are frequently at risk in the course of protecting ours.

Writers and readers love them. Whether thrillers, mysteries, or general fiction, a vast number of law enforcement protagonists fill the books: fighting crime, solving mysteries, saving victims, and often keeping readers up at night. With the launch of my new series of crime-solving mysteries, I decided to begin an interview series spotlighting true professionals in the field with the hope of providing readers with insight into the real world of law enforcement.

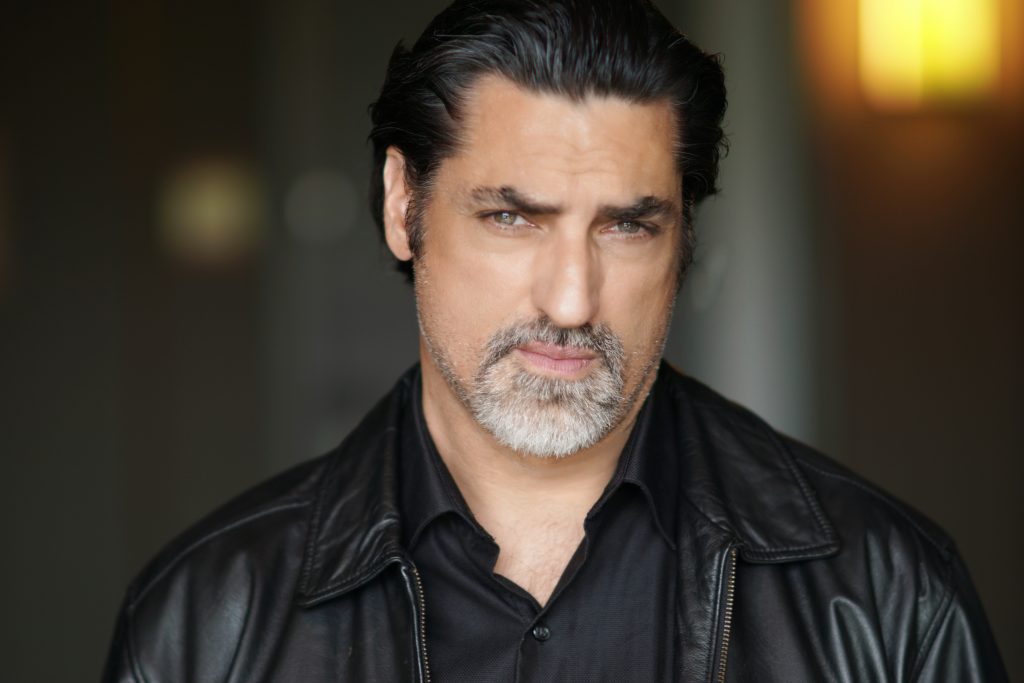

As my first featured subject I am thrilled to have the multifaceted Paul Schad, who is not only a retired detective from the Broward (Florida) Sheriff’s Office, but also an accomplished actor, acting coach, and literary consultant.

Born on Long Island, NY, to a home builder and a homemaker, Paul is the first member of his family to enter law enforcement. His career began with the NYPD, when fresh out of the Police Academy with a two-year degree in Criminal Justice, he was assigned to the 79th Precinct, Bedford Stuyvesant, which at the time was the most dangerous in the city.

In the following dialogue, Paul, in his own words, provides a glimpse of his life in law enforcement.

What was it like growing up in your neighborhood?

I was raised in a middle-class suburb on Long Island. Relatively low-crime, but many of us teens created our own mischief and stupidities – mostly rowdiness, street racing, drinking, etc.

When did you decide to make law enforcement your career?

When I was a high-school senior, I was talking with my church youth group leader who was also a police officer. He told me a college degree wasn’t necessary to be a police officer. That piqued my interest (lol). I learned that you had to be 21 to be a police officer, so then I figured I’d get a job and attend community college in the meantime.

Where did you begin your career?

I started the NYPD academy in July 1984. When I graduated six months later, about 30 of us rookies were sent to a field training unit in Bedford Stuyvesant (79th Pct), which was the most dangerous precinct in NY at the time. That first six months on the street was an eye-opener. There was no shortage of violence, poverty, and despair. As rookies we would compete to see who could confiscate the most illegal knives in a shift (concealed knives with a blade over four inches long are illegal in NYC). It was such a crime-infested precinct, we wouldn’t even arrest them because the Desk Sergeant would hassle you if you got tied up on a knife charge—unless someone was shot or stabbed. We’d just disarm them, send them on their way, and then compare knives and experiences at the end of shift—kind of like a crazy competition among us. That novelty wore off within 3 weeks as it became clear there was no shortage of illegal knives, but the bigger threat was the illegal guns in the area. You need to prioritize efforts in high crime areas, so many lower-level crimes aren’t enforced.

When you began, did you have any particular goal for your career?

I don’t know why, but I never considered rising up the ranks. I didn’t want to be a supervisor, but I wanted to be a detective; to work undercover, working narcotics and eventually long-term OC [Organized Crime] investigations; and then later in my career be a “suit & tie” detective working cases. My career ended up being similar to my goal.

Give us a brief description of your early career.

I was a patrol officer in the NYPD for almost three years before I was hired by the Broward Sheriff’s Office in south Florida. At BSO I worked patrol, and then after about 6 months they would “borrow” me at times from patrol for undercover assignments or surveillances. After about a year, I was assigned to work street-level undercover vice and narcotics investigations. This was the late 1980s, so, when family and friends heard I was working narcotics in south Florida, they automatically think of the TV show Miami Vice and assume I’m driving a sports car, dressed sharp, and going to fancy nightclubs. I’m like no; I’m driving around in a beat-up Oldsmobile, wearing sweaty t-shirts with jeans, going to dive bars and social clubs, and associating with junkies and prostitutes. They’re thinking suave Sonny Crocket, and I look more like Ratso Rizzo from Midnight Cowboy. Rarely did I see the inside of a nice nightclub or restaurant working UC.

What were the undercover (UC) assignments like and why were they given to you?

Working undercover came naturally to me. I had a knack for “shedding” my police role and taking on whatever character was needed for an undercover assignment. I always had a backstory for my character. It could range from portraying a nerd visiting from NJ, nervously visiting a prostitution front, a street level junkie looking for his next score, a low-level mob associate looking to unload stolen goods to anything in-between. Whatever it was, I made sure I totally looked and felt “in the role” and did what was needed to get what was needed as long as it wasn’t illegal or immoral.

Later when I started pursuing acting, I realized a lot of what I would do – the techniques and mindset – were actually Method Acting. The big difference between acting in an undercover role and acting in film is there is no script in UC work, so you have to wing it – there’s no second takes. And UC work – especially working narcotics – is always unpredictable and often volatile.

What was your favorite part of the job?

Being a part in actively DOING something to make the community safer and not just being a bystander. It’s like what they say about sheep, wolves, and sheepdogs. A good cop has a protector mentality. That’s why they are drawn to the law enforcement profession. They are the sheepdogs protecting the sheep from the wolves. Unfortunately, the sheep, sometimes, misunderstands the sheepdogs and their intentions.

To be honest, nothing beats the rush of hunting a wolf—a dangerous predator. I can’t explain it. But whether it’s searching for them or actually chasing them, the pursuit is exhilarating and bringing them to justice is rewarding. Sure, it’s dangerous, but you have the drive and determination to take them off the street and keep them from victimizing again.

When someone is victimized—especially by violent crime—the cops need to.

What was your least favorite part of job?

Often the lack of support from the communities we served and the lack of support from the brass. It’s a government job, so there’s no shortage of wasted or limited resources, misdirected emphasis or policies, and even political correctness that too often derail the process of getting the job done.

What was the most satisfying part of the job?

I would have to say working in the Career Offender Unit where I investigated and tracked convicted sexual predators. Every time I arrested a sexual predator, whether it led to them returning to prison or just jail and getting bonded out the next day, just knowing that for that time I kept them from victimizing anyone again.

What is the fear factor like for police officers?

Most of it comes down to training. When you have adequate and frequent training, you are more confident and that comes through during dangerous situations. Also training and practice helps muscle memory. It’s always better when confronted with a dangerous or an emergency situation to start reacting as you’ve been trained as opposed to being surprised and forced to start thinking how to react. I believe a cop cannot have enough good training.

What effect does the job have on marriage and family life?

In recent years, mental health professionals, as well as law enforcement agencies, are realizing more about the unique stresses of police work on the officer, their spouse, and family. Many turn to alcohol or just keep it all inside, neither of which is healthy. Either way, it ends up affecting the officer and subsequently their family. Some psychologists encourage police to vent to their spouse after experiencing particularly dangerous or shocking situations, but I don’t think that is a good idea most of the time. It might help the cop some, but it brings the spouse into the horror experienced and in turn affects him or her. Like military combat veterans, I think it’s best for police officers not to divulge too much to a spouse, but what might be helpful instead is to spend more time with other police officers who have had similar experiences.

I believe PTSD in LE is more common than people realize, especially for police working in high crime areas and assignments. But cops hide it. Part of it I believe is that sheepdog mentality. They know they are responsible to keep things together and move forward to protect—be it the community they serve, their brothers and sisters in blue, or their spouse. What I’ve been hearing is that many veteran and retired LEOs are experiencing “cumulative PTSD”—meaning not caused by a specific event, but by experiencing numerous violent situations, as well as numerous horrific and depressing situations over 20-30 years. They handle it during their career by burying the memories so they can go on to work and face the same darkness and depravity the next day. Once they retire and are no longer responsible to keep serving in that capacity, the depression and anger starts surfacing. This is a noble career, but not without great unseen costs. I’ve said over the last few years that being an urban cop is a toxic job – do it enough years and it almost feels like it eats away at your soul.

Did your job have an effect on your children?

My sons were only 8 and 10 when I retired and had only become aware of the dangers for a short period before my retirement. Therefore, it wasn’t really an issue for them. My wife and I would also downplay or avoid news about officers injured or killed. Sometimes the schedule keeps you from celebrating holidays with your family, especially when you are newer on the force because shift assignment and time off is usually based on seniority. But on the flip side having days off in the middle of the week can sometimes make it easier to schedule doctor’s appointments, maintenance and repair work, etc.

Would you want a child of yours to follow a career in law enforcement?

Probably not—not where we are at now with the common anti-police rhetoric and policies of the media, politicians, and even the courts. And never before have the police – and their families – been under such attack. It doesn’t make the news much, but there has been an increase in threats, harassment and even violence against police officers’ families.

If you had it to do again, would you follow the same path?

There were times I’d be having fun at work and think, “I can’t believe I actually get paid to do this,” and then during the dark or dangerous times at work I’d think, “They can’t pay me enough to do what I’m doing.”—and then of course going forward and handling the situation. Two totally different attitudes to different circumstances—the latter occurring during tragic or dangerous situations. There were times when I’d seen and experienced enough and wanted to leave the job but always stayed because I knew if I left this career, the problems would still be there, so I might as well stay and try to continue to help in my role. So, the bottom line—yes, I would do it all again.

What changes have you seen in police work since you began your career?

The idea of “de-escalation techniques” is very important and useful – in limited situations. The training and policies now have totally gone overboard and actually, unintentionally, encourage a violent person to continue in their threats. De-escalation techniques are beneficial when people are upset and sometimes when they are angry. They are not helpful when someone is threatening or engaging in violence. I’ve noticed stern commands have been replaced with pleading. Sounds good on paper, but totally unrealistic in real life.

If you are pointing a gun at someone and they are walking towards you with a knife, the tried-and-true response is to take a few steps back, or to the side (to create distance), while pointing your gun at the suspect and clearly making a short and direct COMMAND. (“Stop! Drop the knife—NOW!). But if instead, you continue to back away with your gun drawn and plead with them (“Please—I don’t want to shoot you. Please, sir – stop. Please, sir!”), they have no reason to stop – and they don’t. A person intent on violence in that situation will not stop because you back away and plead with them even if you are armed. However, if they believe that you will use deadly force against them if they don’t do what you command them to, then they are very likely to stop out of fear. It’s basic human nature under those circumstances.

Are police officers effected emotionally by any of the work?

Of course – we’re all human. At first you learn not to show it, and then you learn not to feel it.

Do those in the field have a sense of humor?

Yes. Like most first responders and the military, there is that dark or black humor. It’s very twisted and could be shocking to people that just don’t understand. But it is a way of coping with the frustration.

Do police detectives ever collaborate with PIs?

Usually, it would be PIs reaching out to detectives. I had it happen in two cases, and they were both thefts that insurance investigators had intel indicating the theft reports were fraudulent. With their investigative leads, I was able to pursue prosecution in both cases.

What personality type is best suited to police work?

Not suited would be someone passive. Let’s face it. When a civilian calls 911 because someone is being aggressive or violent, they want the police to respond, to take charge, and to restore the peace. You can’t depend on a passive person to effectively do that in that situation.

What do you think the public needs to know about police work?

A few things. First, we don’t make the laws, nor are we the jury that determines innocence or guilt, nor are we the judge who implements the sentence. Second, we don’t make our department’s policies. Third, and most important, we are human beings that often need to make split-second decisions with little information that can cause life-changing reactions.

Looking at the contemporary scene, what do you believe is working and what isn’t?

Like I said before, the new de-escalation techniques are a failure—and dangerous.

What is working is the big advances over the last ten years when dealing with people with mental health issues. It was long overdue, but gladly welcomed. I was proud to be among the early classes in the Broward Sheriff’s Office to be specially trained for a part in the Crisis Intervention Team. As time went on, all police officers received this training. We learned how to talk and relate with someone when they were experiencing a mental health crisis to diffuse situations and get them the help they needed. This in itself was a type of de-escalation techniques, but as stated earlier these techniques are usually not helpful when someone is actually engaged in violence.

What is the most important skill and or quality a good police officer needs to have?

Common sense and professionalism. And—guts! (he laughed)

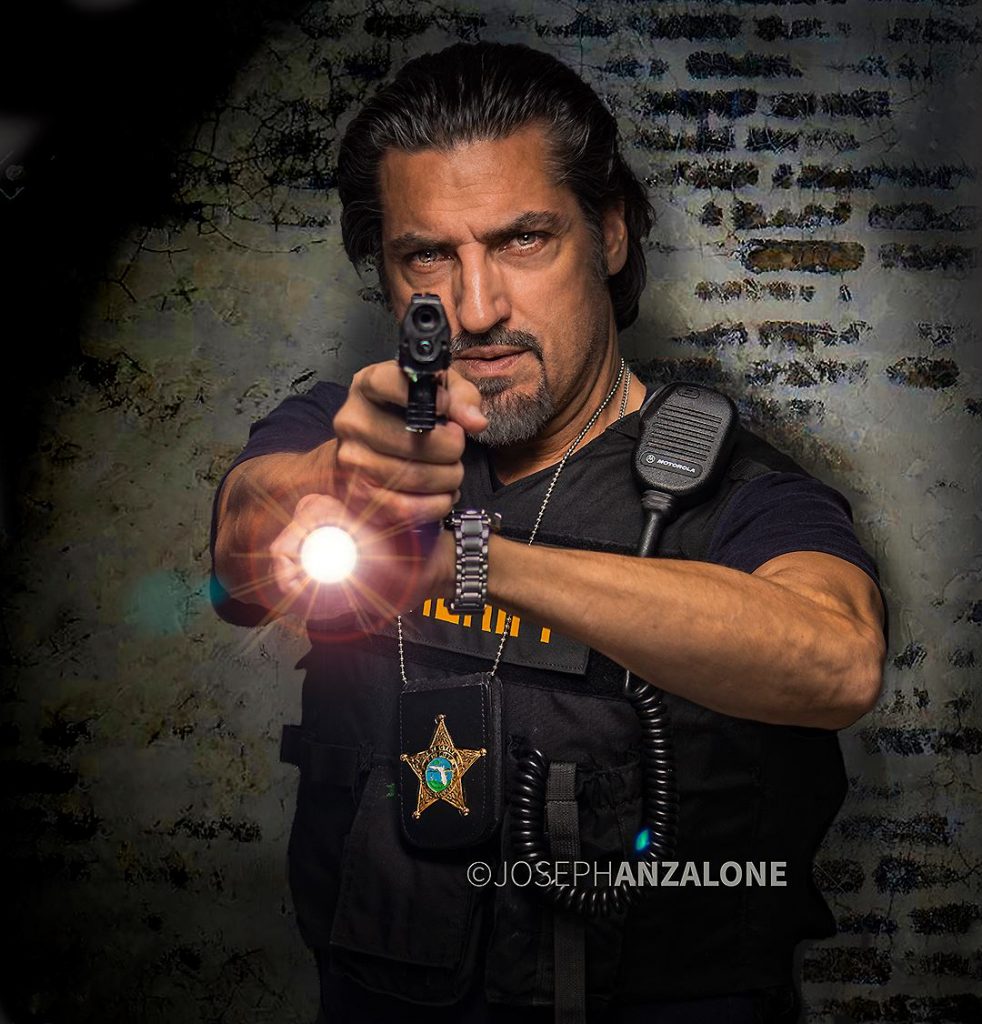

Moving along to your acting career, tell us a little about your work.

I have portrayed various law enforcement officers, but I actually enjoy roles where I am the bad guy, and that is what I’m striving for (mobster, biker, pimp, drug dealer, etc.). This week, I’ll be portraying an outlaw biker for a tv pilot. I enjoyed playing bad guys when I worked undercover to catch criminals, and now I get to do it for entertainment – in safe environments! (he laughed)

How accurately are the police portrayed in movies and TV?

Wow, so much in television and film has it wrong when it comes to law enforcement policies and procedures – I’d say almost 90%!

One film, starring two famous stars as NYPD detectives, has them throughout the film armed with Glock pistols and several times “cocking” their guns with their thumbs every time they pulled their weapons . Problem is Glocks don’t have a hammer like that, so it is impossible to cock them.

In other films, it is common to see firearms being held or handled wrong, and tactics that look dramatic but are totally incorrect and actually unsafe in the real world. But the viewers see these wrong things all the time and believe them to be correct. And let’s not forget the bad guy is always apprehended before the show ends!

Do any films or TV shows get it right?

Starting with the movie Bullitt (1968) and The French Connection (1970), Hollywood began to turn out gritty, realistic police dramas. These films had Police Technical Advisors and were filmed mostly on location in the crime-ridden cities where they took place. Serpico (1973), Report to the Commissioner (1974), Fort Apache, the Bronx (1981), Prince of the City (1981) are just a few examples of accurate Hollywood projects. By the late 1970s and 1980s, however, most serious police dramas were replaced with unrealistic action heroes that were virtually indestructible (which helped in making lucrative sequels), including the franchises of Dirty Harry, Lethal Weapon, Beverly Hills Cop, and Die Hard—fun movies—but not as accurate about crime or law enforcement.

From the early 1970s Hollywood also brought us gritty realistic crime dramas such as The Godfather (1972), Taxi Driver (1976), and Goodfellas (1990).

A more recent film that I thought was very accurate to urban policing (with the exception of an exaggerated shootout at the end) was End of Watch (2012).

Do you have any recommendations as to resource material on law enforcement?

I find biographies about law enforcement officers are a good source. Authors I recommend are Peter Maas, Robert Daley, Joseph Wambaugh, and Florida’s own Cherokee Paul McDonald.

What classes are you currently offering?

I teach two types of workshops: Police Academy for Actors, and Police Academy for Writers. In both workshops I have students try on and handle equipment (ballistic vests, gun belts, prop weapons) and get acquainted with them. I also teach basic tactical movements and procedures.

For the actor’s class, I focus more on getting them use to wearing and handling the equipment and looking the part. In addition, I give tips for auditioning as a LEO. The actors learn a lot and gain confidence for auditions and on-set acting.

For the writer’s class, I focus on the feel, sounds, and smells related to law enforcement actions, as well as tactical responses and investigative procedures. This can’t be learned from watching movies or documentaries.

With COVID the workshops have been put on hold, but I am working on arranging to teach the next one in early 2021.

I also do one-on-one consulting with authors, actors, and screenwriters, as well as on-set film consultation.

AUTHOR NOTE: I can personally vouch for the value of taking one of Paul’s classes and consulting with him. A scene in the book I’m currently writing is much better as a result of Paul’s input.

To learn more about Paul, enroll in a class, or contact him, see the following:

Web site: www.paulschad.com

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/paul-d-schad-78690178/

IMDB-Pro: https://pro.imdb.com/name/nm1816506?ref_=nm_nv_mp_profile

Judith Erwin is the award-winning author of seven novels. A retired family law attorney, she worked extensively with law enforcement and experts on psychology and addiction over the course of her 22-year career.